- Home

- Crete History

- Sir Arthur Evans

This page may contain affiliate links, see our disclaimer here.

Sir Arthur Evans

By Katia Luz

Archaeologist of Knossos Palace, Crete

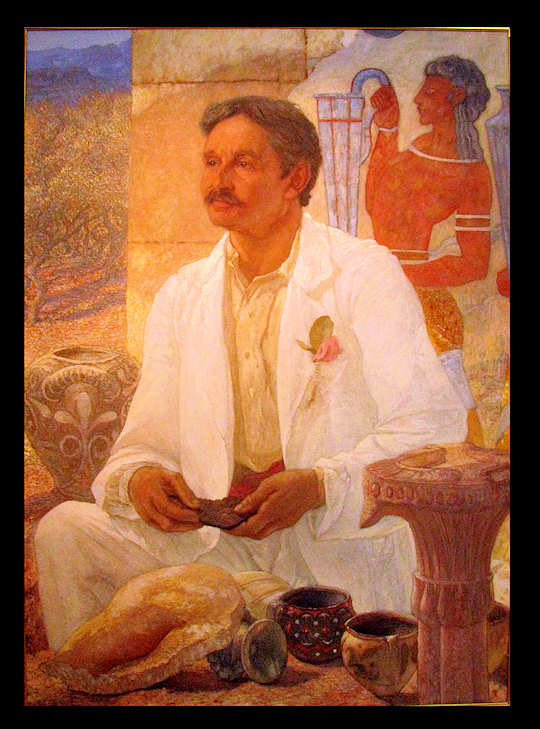

Sir Arthur Evans portrait (image by Martin Beek)

Sir Arthur Evans portrait (image by Martin Beek)Biography by Apostolis Heretis-Hadoulis

Sir Arthur Evans was a

distinguished scholar and archaeologist, intimately involved with Knossos

Palace in Crete, he was its champion and faithful recreationist.

In this age of very fast trains, planes and even faster emails, of rapid money transfers and next-day-delivery courier services, it is hard to truly understand the magnitude of Arthur Evan's achievements in archaeology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

He not only revealed a hidden civilisation, he named it and created the dating system by which we categorise it, all in a time before cars, concrete or cash machines.

Sir Arthur Evans - Early Life

Arthur Evans was born on the 8th July 1851, in Nash Mills, Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire, England.

He had two brothers, Lewis and Norman, and a half-sister Joan. His father was John Evans and his mother was Harriet Dickinson. His father was a successful paper manufacturer, operating The John Dickinson and Company business, which came to him through his wife's (and cousins) family, the Dickinson's. They were a family of great wealth.

Evan's father, and before him his great grandfather, where learned men, interested in knowledge and antiquity. They, as well as Arthur's uncle John Dickinson, were members of The Royal Society.

John was a budding archaeologist, with a study overflowing with flint and bronze. He took the young Arthur on flint collecting expeditions in Britain and France. Arthur took on his father's interests, although in his own way. Arthur admired knowledge and education, and he loved collecting coins in place of flint.

Evans studied history at Harrow and Oxford, and later at Göttingen.

Evans was extremely short-sighted, which worked as a great advantage for him over the years. He very reluctantly wore his glasses. Items held a few inches away could be seen in almost microscopic vision. Even faint signatures of artist's names on coins could be discerned if he held them close.

Evans was not a sporting man, he was opposed to organised team sports. He was a physical, fit man who loved to travel. In this he was quite unique for a man of his class, as he loved travelling off the beaten track and roughing it.

In 1871, when only 20 years old, Evans travelled to Bosnia and Herzegovina. He became enamoured with the south Slavic people and the natural landscapes; the Dalmatian coast, their architecture, and their culture which was a blend of Roman, Byzantine and Moslem. A hearty, proud and tough people.

Biography of Sir Arthur Evans

Architecture was the passion of Sir Arthur Evans whose

life's work was the archaeology of Knossos in Crete, Greece. He restored, and

in many places reconstructed, the site and added touches of colour to the Palace of Knossos which

remain controversial to this day.

Here in our biography of Sir Arthur Evans we explore his early life before he

arrived in Crete and Greece and made such a significant contribution to ancient

Greece architecture.

In 1871,

when only 20 years old, Evans travelled to Bosnia and Herzegovina. At this

time, Bosnia and Herzegovina where under Turkish rule. Arthur became a Liberal

and followed the ways of Gladstone, a man his father detested. In 1872,

Arthur went mountaineering in Rumania and Bulgaria with his brother Norman. In

1873, he toured Sweden, Finland and Lapland. In 1875, he returned to Bosnia

with his brother Lewis, where they were arrested as Russian spies. The Slavic

people and their struggle for freedom connected with Arthur.

Evans had decided that he did not want to pursue the family business. Instead

he pursued an academic career. After a few rejections from various colleges for

conventional roles, Sir Arthur became Special Correspondent in the Balkans for the

Manchester Guardian. He was chosen by then editor, C.P. Scott. Evans was based

in Ragusa. Over many years, his letters to the magazine where seen to be so

potent they were published as a book. While on the field as a journalist, he

still made the time to excavate Roman buildings in the Balkans.

During these years, he took to using a walking stick come to be known as

'Prodger'. This was to assist Evans due to his near-sightedness. They

were to never be separated.

The British Consul was far from fond of Evan's work, due to their brutally

honest depictions of events transpiring in the region. This made their slow,

ineffective diplomacy look bad. When they criticised Evans, he lunged deeper

afield for more proof. He went to burnt out villages, made lists of the dead

and names of victims. He put himself through great physical danger to obtain

the information he wanted to reveal. Just one illustration of this was his

crossing near-frozen rivers whilst naked to access remote villages, to report

on the local situation. This new evidence could not be ignored.

An old Oxford friend, Freeman, came to visit Evans at Ragusa. His sister Margaret, also came on this trip. She met a tanned and toned Arthur Evans, who she came to fall in love with. They were to eventually marry, celebrating their engagement by visiting Schliemann’s Antiquities of Troy in London.

Soon after their marriage, Arthur and

Margaret bought a Venetian house in Ragusa, Casa San Lazzaro, where they were

to live for a number of years.

Still correspondent to the Manchester Guardian, he delved into the history,

antiquities and politics of the Slavic people, and also began directed a

portion of his focus on archaeological excavation and buying Greek and Roman

coins.

Ultimately, Margaret could not settle in Ragusa. The conditions too difficult

for her. Although, as fate would have it, they would leave Ragusa, but not as

Arthur would have liked. Austria, the now ruler of this region, kept a keen eye

on Arthur Evans. They held him in the same regard as the Ottoman empire did.

After they confirmed that he was meeting with insurgents at his home, both

Margaret and Arthur were arrested. They were both later released yet expelled

from the country.

Sir Arthur Evans Visits Greece

In a tour of Greece in 1883, Evans met the

infamous archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. Evans was fascinated by ancient

Greece architecture and especially with the gems found at Mycenaean sites.

These seemed older than science had suggested to Evans, and not made by

Mycenaean hands, as the approach and style was altogether different. In not,

then by who?

Sir Arthur Evan’s curiosity led him to Crete, and luckily for those of us with a love of

ancient Greece architecture and Cretan history, it led him to Knossos. Evans

would ultimately spend the next 30 years excavating, reconstructing and

annotating his finds at Knossos, as well as rediscovering the long lost Minoan

civilisation.

At the age of 33, Arthur Evans was appointed the Keeper (curator) of the Ashmolean Museum. At this point it was a run down and neglected museum. It could not have come into better hands. A great number of fine artefacts had been borrowed by other museums. These museums felt the full brunt of both his determination and sharp mind. Many of his letters would eventually cut through the bureacracy and reluctance of these museums. He pored over hidden artefacts in the store rooms of the Ashmolean and now proudly and respectfully displayed them, many of them quite rare and unique. Using his personal network, he came to display Drury Fortnum’s Renaissance collection at the museum.

Sadly Margaret was to pass away in 1893. Previous illnesses and her time in rugged Ragusa caught up with her.

In a tragic way, Margaret's passing allowed Evans to pursue interests that he otherwise may not have been able to.

Minoan Seal Stone (image by Andree Stephan - Own work, CC BY 3.0)

Minoan Seal Stone (image by Andree Stephan - Own work, CC BY 3.0)

Shortly after Margaret’s death, Evans was rummaging through trays of antiquities with John Myres in Greece's Shoe Lane. Here he came across 3 and 4 sided engraved stones. These were stones and gems engraved with symbols and hieroglyphs. They were drilled through. Traditionally, a string was passed through and these were worn around the neck or wrist.

Later, these were worn by Greek woman, believing them to assist when weaning children, hence them being called milk stones. Evans, with his microscopic vision, studied these for hours. They were said to have come from Crete.

Sir Arthur Evans Arrives in Crete

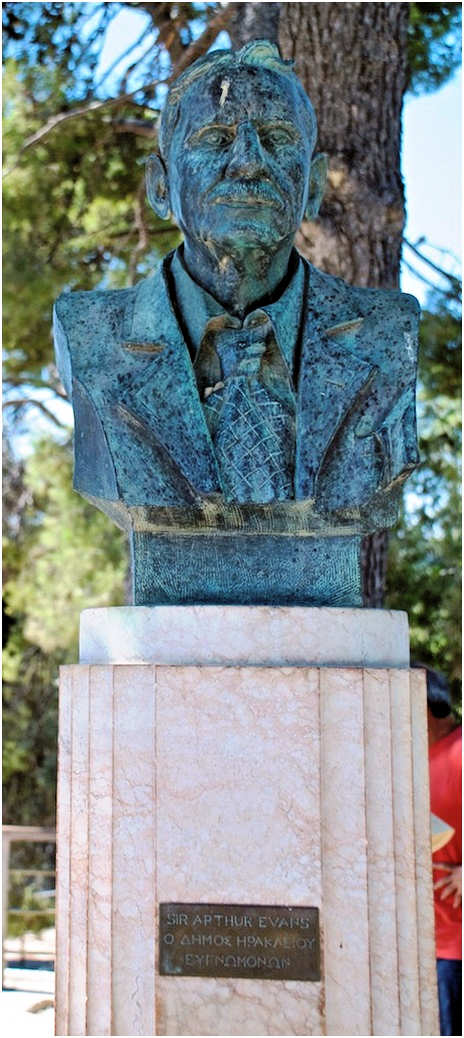

The bust of Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos Palace Archaeological Site, Heraklion, Crete

The bust of Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos Palace Archaeological Site, Heraklion, CreteIn 1894, Sir Arthur Evans first sets foot on Crete. He instantly felt at

home. Again was he surrounded by a hearty, passionate people unwillingly

under Ottoman rule. He adored the blend of Venetian, Ottoman and

Christian architecture.

Proclaiming he was acting on behalf of “The

Cretan Exploration Fund”, he purchased a share of the site at Knossos

from the Turkish land owner. Little did they know this fund was not in

existence yet. Although within years it was to in fact come into reality

with none other than Prince George of Greece as Patron.

Between 1894

and 1899, Sir Arthur Evans was to explore parts of Crete, including Psychro cave.

He constantly came across these milk or seal stones. In 1898, he again

contributed to the Manchester Guardian, reporting on the conflict in

Crete, criticising both the British and the Turks for their behaviour.

In

March of 1900, he returned to Crete with his sleeves very firmly rolled

up. With him he had D.G. Hogarth, an experienced archaeologist, and

Duncan Mackenzie, a seasoned excavation record keeper, a man of many

languages and great character. He employed locals to dig on site. He was

later to be joined by Theodore Fyfe, an Architect with the British

School of Archaeology at Athens.

For Sir Arthur Evans' entire time at Knossos he

was to have an architect on site. A rare and very beneficial skill to

have at hand. Fyfe, over the years, was to be replaced by Christian Doll

and then Piet de Jong. As Crete was being handed over to the Greeks,

Arthur purchased the entire site at Knossos from the fleeing Turkish

land owner.

It was Arthur Evans who gave the ancient inhabitants of Crete the name of Minoan, after the legendary Cretan ruler King Minos.

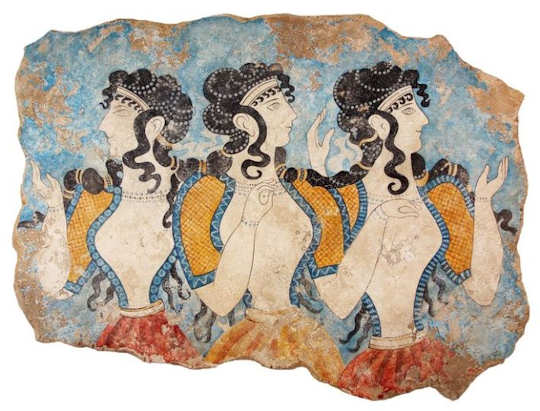

Shortly

after, they discovered the very first true image of the ancient

inhabitants of Crete. They found fragments of a fresco of the Cretan

youth, athletic and slim waisted, brown-skinned with combed long black

hair carrying a rhyton.

A Swiss artist, Emilie Gilliéron, and later his son, also Emilie Gilliéron, was employed to assemble the tiny fragments of artefacts. He was to make the missing places, enabling us to see the work as a whole and complete object.

Many reproductions of earthenwares, frescoes, shields and thrones where made and left in situ giving us a clear and concise image of the palace of Knossos. As the originals were taken and protected in the Heraklion Museum, we would not have had anything on site to illustrate how the Minoans lived and decorated their living environments. This is where Sir Arthur Evans was a genius. Although his techniques were seen as untraditional, his reconstruction, not excavation, of Knossos has given us a glimpse into this rich, colourful, artistic and peaceful race that had literally been forgotten. In the 1920’s, when concrete was introduced, he could very easily reproduce the buildings on site with the building materials in situ. The grand staircase with its intelligent and sophisticated plumbing is testament to this fact. A partly reconstructed stair, with detailed stones in the museum, would not give us any indication of the finesse of the Minoan craftsmen and masons.

Sir Arthur Evan was to also create the dating system to which we date the period of Minoan civilisation. This was to be amended and extended over time, but his system nonetheless.

In 1906, Arthur built the Villa Ariadne on site. This was to be both his living quarters, writing studio and workshop.

In

1908, his father passed away leaving Arthur the greater percentage of

his fortune, and within months he was to also inherit the Dickinson

estate from his cousin, leaving Arthur far wealthier than his father had

ever been.

Sir Arthur Evans wanted control of his excavation at Knossos,

and though some funding had initially been coming from the Cretan

Exploration Fund, this soon dried up. He was for thirty years to work at

Knossos, and this was made possible by initially his father's and then

his own personal contribution. Arthur was to solely fund all works at

Knossos for most of his time there. This also gave him the freedom to

conduct himself as he wished.

Over the years he wrote the great four-volume book of his finds at Knossos. Sir Arthur Evans wrote “The Palace of Minos” with a quill pen, using neither a secretary nor a typewriter.

In 1911 at the age of 60, Arthur Evans was knighted for his contribution to learning and science.

Sir

Arthur Evans lived at his house on Boars Hill, Berkshire for his last

years. He created great gardens surrounding his home, still delighting

in nature and the outdoors. He died on the 11th July in 1939, three days

after his birthday at the age of 90.

Ladies in Blue fresco from Knossos Palace

Ladies in Blue fresco from Knossos Palace Large pithoi at Knossos Archaeological Site

Large pithoi at Knossos Archaeological Site

Visiting Crete's Minoan Palaces

Getting Here

Take a 1 hour flight from Athens to Heraklion with Aegean Airlines or Olympic Air, with many flights available per day.

Or take a 9.5 hour overnight ferry from Pireaus port of Athens to Heraklion port.

More on flights and ferries below.

Car hire in Crete is a really good idea as it is a large island 60 km by 260 km. There is so much to explore.

When you book with our car rental partners - Rental Centre Crete - you are supporting a local company with excellent service and easy online booking. We are sure you will be well looked after by the team. Choose from hybrid, electric or regular vehicles.

We trust you have enjoyed these tips from the We Love Crete team. Evíva!

Yiásas!

Anastasi, Apostoli & Katia

are the We Love Crete team

We just love sharing our passion for Crete, Greece and travel

About us Contact Us Kaló taxídi!

About the Team

Yiásas!

Anastasi, Apostoli & Katia

are the

We Love Crete team

We just love sharing our passion for Crete, Greece and travel

About us